The things I will do to defend an ugly top

I love how the vest called out to me at 5.48pm on 20 March 2024 in the ABBA Voyage merchandise shop in East London. A recycled fibre mix draped over a wooden bust. Neon-yellow, black-rimmed letters emblazoned across poppy red and hot salmon checks. A-B-B-A. XXL. The only size left. A perfect fit.

I love how the vest’s quadrangular shape whispered to me that I would never feel that lower back chill again, on days that call for naked arms but double layers around my midriff (i.e. every other Tuesday in the UK). Offering all the benefits of a gilet but without raising questions about my attitude towards hunting.

I love how the vest was expensive enough for me to believe that some of my money would actually go towards fair payment to the garment workers who made this piece of art. The discrepancy between the product’s material value and its price not so great as to raise serious questions about its distributors’ integrity.

I love how the vest screams out against the blue-grey of the Great Northern branding on my commuter train. And the blue-grey jacket of the man in front of me. And the blue-grey shirt of the men next to him, and the one next to him and the one next to that one. An arresting feature as we all speed in the same direction.

I love my vest because I’m not even that big of an ABBA fan. Because I love it in spite of its logo. And because that makes me deeply layered.

I love how this vest can be read as a take on the concept of kitsch.

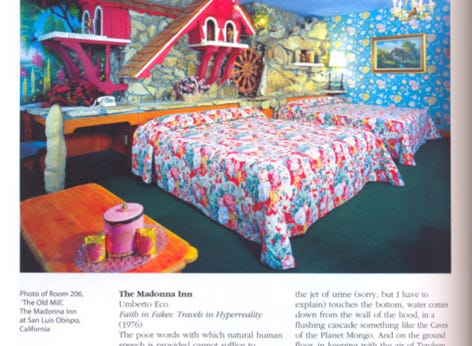

‘Kitsch is a work that, in order to justify its function as a stimulator of effects, flaunts the outward appearance of other experiences’ (Umberto Eco, On Ugliness, p. 405).

I love how my vest goes against the implied criticism above that kitsch is mere imitation as if that was somehow a bad thing. I love the fact that I can wear something that lets me bring traces of the outrageous 2-hour ABBA hologram show I saw to my drab 9-to-5 existence (which I need to lead to be able to afford the outrageous hologram show #CircleOfLife).

‘Those who like kitsch believe they are enjoying a qualitatively high experience (Eco, p.398).

I love how my vest complicates Eco’s surprisingly patronising notion of what it means to be a kitsch lover. Not only do I believe that I have a qualitatively high experience when wearing my kitsch vest. I am having a qualitatively high experience. I feel awesome in my vest.

I love how the vest made me understand for the first time the difference between kitsch and camp and how the vest can be considered an example of the latter.

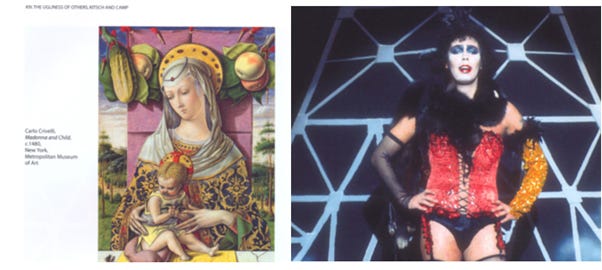

Camp is not measured by the beauty of something but on the extent of its artifice and stylisation … To be camp, objects must possess some exaggeration or marginal aspect … as well as a certain degree of vulgarity, even when there is a claim to refinement … Camp is also, but not always, the experience of kitsch of someone who knows that what he is seeing is kitsch (Eco, p.409f.)

I love my vest but lurking beneath all my adoration is a suspicion that the only reason I can love it so is because I am otherwise compliant with mainstream aesthetics. Its garishness highlighting my conformity.

[Camp] is a manifestation of aristocratic taste and snobbery and as the dandy is the nineteenth century’s surrogate for the aristocrat in matters of culture, so Camp is the modern dandyism. Camp is the answer to the question: how to be a dandy in the age of mass culture? But whereas the dandy sought out rare sensations, not yet profaned by the appreciation of the masses, the connoisseur of camp is fulfilled by the coarsest, commonest pleasures, in the arts of the masses. The dandy held a perfumed handkerchief to his nostrils and was liable to swoon; the connoisseur of Camp sniffs the stink and prides himself on his strong nerves (Eco, p.411).

Hipster negatives garnished with elitist posing. Do I not love my vest but rather its common acrylic fibre smell?

However, I love my vest without irony. Which apparently is the way to love camp without being a snob.

[Ugliness] is only [camp] when the excess is innocent and not calculated. Pure examples of camp are not intentional, but extremely serious (Susan Sontag in Eco p.418f.).

(I think this essay is a case in point about my level of seriousness about the vest)

I love how the vest makes manifest my yearning for something other than algorithmic-designed, Instagram cookie-cutter ideas of edginess. And how that somehow echoes what Sontag wrote 60 years ago:

Camp turns its back on the good-bad axis of ordinary aesthetic judgment. Camp doesn’t reverse things. It doesn’t argue that the good is bad, or the bad is good. What it does is to offer for art (and life) a different – supplementary – set of standards (Sontag in Eco, p. 417).

My vest: camp in acrylic fibre.